Where Conviction and Insecurity Collide: Religious Overtones (Part 5)

This is part 5 of the series “The Place Where Conviction and Insecurity Collide”. See original post here.

COLLISION: Religious Overtones

Many readers were shocked at how overtly religious the third installment turned out. The reviews quickly proved it. Bittersweetly, I found myself chuckling while reading their varied analysis and clinical breakdowns—had they been paying attention, they shouldn’t have expected anything less.

It’s true: I write from a distinct worldview, that I cannot, nor should not, deny. Yet in the same type, I grant opposing worldviews to most of my cast. By this I admit an inherent bias. However, not one that devalues every character who does not share my own. Dmitri, our frail and philosophical kingling, for instance, gifts the series most of its best lines.

Cracking the stiff, well-anticipated spine of Book 3, the reader is quickly blasted with a storm of trials as trailing a ragged Quadren of advisors, they tiredly trudge into Orynthia’s secretive theocracy. Light abounds, exposing shadows even uglier than those left behind. Lore is illuminated. Rites are observed. Feasts are held and fasts are broken. Religion permeates the soil, sanctifying each blade of grass and crunch of snow.

But Boreal was not named by the earth it inhabits.

Nor those who guard its tiny breadth. An inherent logic perfumes the air, holding all things together. It dwells, and unperturbed, unconcerned and unrivaled, does not apologize for its dwelling.

Orynthia is a beautiful melting pot—a patchwork of territories, terrains, political systems, and people groups. Yet just like we see today, the call for an open-minded utopia makes a lot of pretty promises it does not, and cannot, keep. Utopia tries to convince us that human arguments are mere misunderstandings; parties talking over each other but never really listening. That arguments simply boil down to a lack of empathy. A clash of emotions, rather than their source.

English rock and roll guitarist Steve Turner cheekily put it best, expressing a premise that most people have comfortably come to accept: all “religions are basically the same…they only differ on matters of creation, sin, heaven, hell, God, and salvation”[Poems, 1968-1982].

It’s a funny line. The trouble is that those definitions have a pesky habit of, well, defining everything else.

“All human conflict is ultimately theological.” ~Henry Edward Manning

Why rely so heavily on religion in the series? For starters, incompatible religions provide diversity of thought. Diversity of thought demands disagreement. Disagreement promises conflict. And there we have our series sweet spot.

Welcome to The Haidren Legacy—a tumultuous play at getting along.

If Orynthia’s haidrens are to ever forge unity among the Houses (nevertheless at their king’s table), religion requires they find grace for those operating outside their own tenets. A feat much harder to do with someone you cannot convert, no matter how tasty the food.

This is what makes politics, even in fantasy settings, so palpable. Everyone is viscerally different. If we think of a character as being fashioned like a prism, their agenda can only ever be seen one side at a time. Whereas cuts of experience, doctrine, and ritual shape the rest. Light (or in this case, the story) shines through the prism, refracting complex patterns across the page. But what exactly informed these patterns? And how, amid their complexity, can it all make sense?

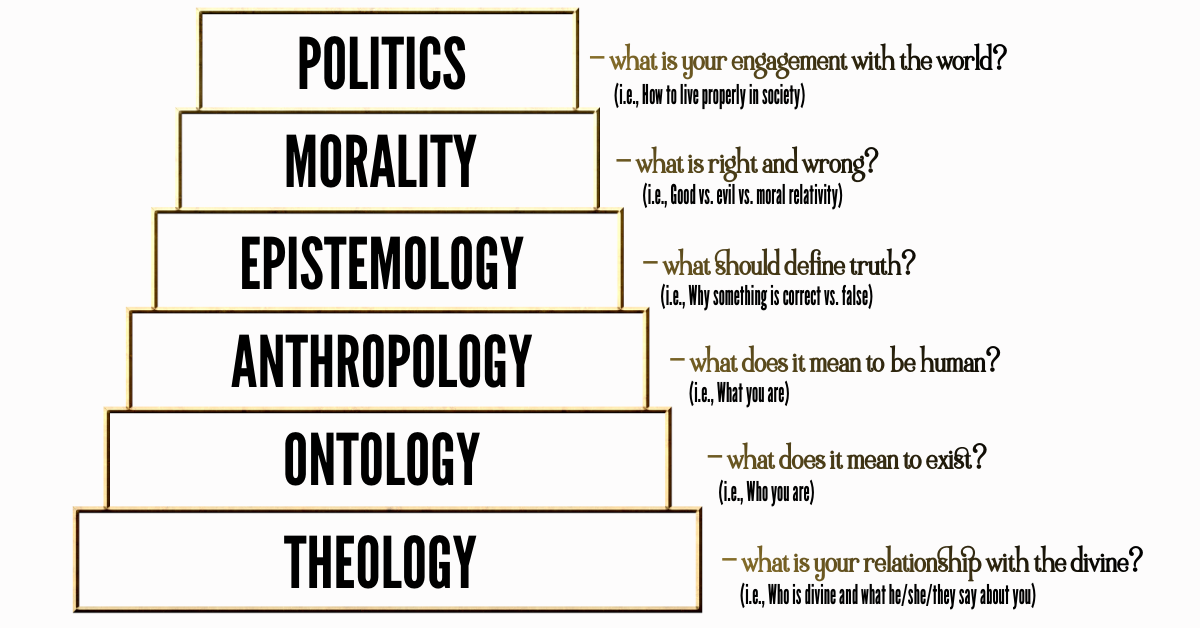

While I wish I could cite my original source, this patristic pyramid provides a ready-made explanation. Here, Aquinas-style thinking maps the funnel of human thought. Worldviews bind cultures, tribes, and people groups together. They aren’t born overnight. Nor do they change with the season. Worldviews are ingrained.

Identity informs behavior, remember? (see blog post here) What we believe about life’s most fundamental aspects mold who we are and how we operate. A person’s epistemology—how they define truth—dictates what they find decent vs. morally reprehensible.

For instance, if someone believes that truth is defined by their own personal history (say, a record of wrongs committed against them), then their morality constitutes a sliding scale stretching from unjust to the justifiable. In other words, that which is not allowed to happen to them, but might be allowed to happen to someone else. Whereas that same scale doesn’t compute for someone who, lower on the pyramid, believes that their gods will punish acts of retribution. Conversely, should a person make offerings to a goddess who is heralded for seeking the revenge of her cosmic lover, then all’s fair in love and war.

People are not numbers, Luscia tells Hachiro at the open of HOBL.

But people sure do take the shape of their ideas.

The same is evident of our characters. No wonder the Quadren struggles to see eye to eye; their vantage isn’t the issue. It won’t matter how much they crouch or contort. Worldviews color everything we see.

HAIDREN TO PILAR

I use Hachiro as the first example, frankly because I adore him. In Sheldon-esk fashion, our scholarly aficionado is crucial for reader discovery while traversing the Orynthian map.

Writing his interpersonal conflicts is easiest. Studying Hachiro’s pyramid, we see why he gawks at religious practice among neighboring Houses. Better yet, how often he will laugh at their absurdity. To him, any argument not steeped in statistical assurance is just that—absolutely absurd. Though this same thinking is what challenges Hachiro to sometimes see people as people, and not numbers on a chart. To our pragmatic shoto’shi, people are replaceable, simply cogs in a greater machine. He can’t quite articulate what gives them meaning, not individually apart from genetics, and therefore struggles to rationalize why one might sacrifice for a person the law would otherwise overlook. Hachiro cannot yet perceive that this also poses an absurdity of his own making.

“Those who can make you believe absurdities, can make you commit atrocities.”

~Voltaire

What we believe about the divine, thus what we believe about ourselves, consequently informs how we will treat everyone else. Beyond that, those beliefs inform what we will live and die for. What stands us taller. What bends our knee. The power we cry out to the dead of night. The power that embodies the dawn.

Forced Hegelian dialectics, like those promoted in modernity, mandate we strip away our distinctions until we look more alike. Sometimes, for the sake of “agreement”, going as far as to pretend that we mean the same things when we most certainly do not. As if “higher truth” will magically hammer out contrasting convictions. Hegel’s dialectic will never work, not for long as least, because conclusions are not determined by their end. They are determined by their beginning.

And that is why on a king’s Quadren, as in circles of our own, discussions get messy. Even if that king is a peace-maker at heart.

KING OF ORYNTHIA

Everyone adores Dmitri. So much that they tend to overlook his contradictions—even his ulterior motives. Our beloved, botany-besotted leader is borderline obsessed with his royal legacy. Readers, and characters alike, interpret this as a humanitarian cause…although looking deeper, we cannot be so sure. Moving down his pyramid, we find that Dmitri is wrestling with a cosmic question. He senses that there’s a creative harmony to the universe, but does not know its source. This is partly why he wishes to bring people together; he can only reason that doing so would bring him into that harmony as well. Orynthia’s king governs pluralistically, not necessarily because he is tolerant, but because he is desperate to identify his own significance. His anthropology compels him to explore this with those most intelligent, religious, or wise. At times, even a drunk nobleman named Ira.

Dmitri embraces a kind of Hermetic worldview where many roads might lead him to the one profundity he seeks. For were he to rule a single road out, he might be cut off from the most important mystery in existence. One leaving him insignificant, alone, and forgotten.

HAIDREN TO BASTIION

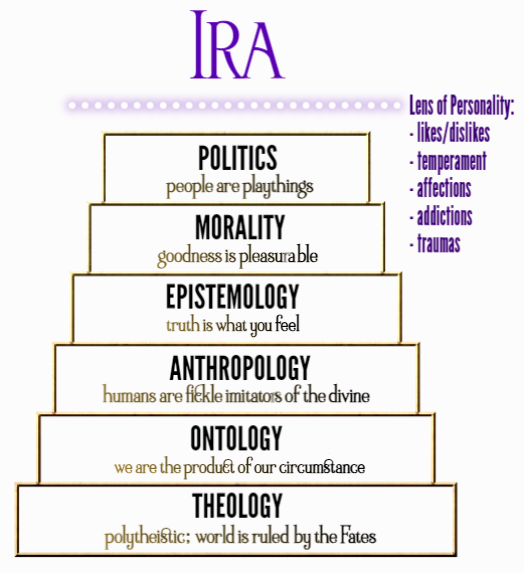

I admit that Ira typically serves as a much-needed comedic relief to the series, though as some suspect, the yancy does play a more purposeful role than his routinely inappropriate joke.

“We become what we behold.”

~Marshall McLuhan

Seemingly simple-minded, Ira may be one of the most straight-forward characters among the cast; his mode of operation uncontradictory. Like his fellow Unitarians, Ira believes in the twelve Fates, a dodecahedral of power, who essentially toy with the destiny of mankind according to their every whim. This implicitly impacts Ira’s outlook. He is created by fickle beings, so fickle he is entitled to be also. Pleasure becomes synonymous with morality, for to Ira, how can something painful be good or just? According to his pantheon of deities, “truth” changes with their next impassioned tide. Feelings are his only compass—that and Gregor Hastings, lest he be cut from the will. Until then, he has little to do but live life as gleefully as possible…just like the Fates, reigning capriciously above him.

HAIDREN TO DARAKAI

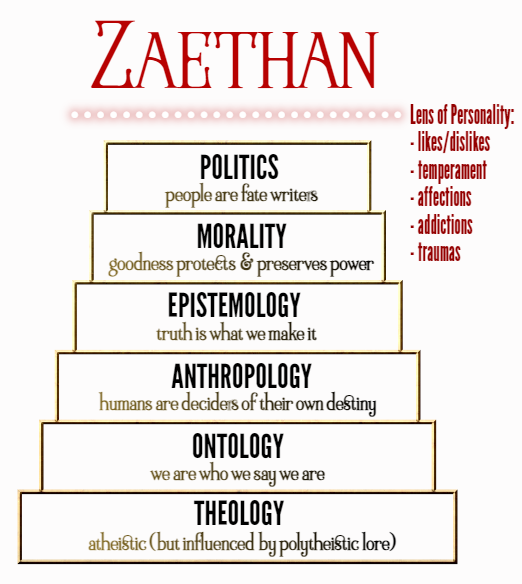

Zaethan is a punch of fresh air. A real punch to the gut too.

To Darakaians, especially those who retain their rich cultural lore, strength is perceived good and weakness wrong. Might defines morality. Those who won’t fight, whatever the battle’s cause, deserve their end. This is why Zaethan is so hard on himself when his entire social structure eventually comes tumbling down around him. He didn’t cause the crash—yet he feels responsible to make something out of its pieces. The very mindset that grants him resilience and self-reliance makes him equally hard on everyone else.

This plays out most bombastically through his politic. Zaethan wants to charge through every dilemma, often battering against his “frenemy” Luscia. He cannot, no matter his level of empathy, understand her motives. Yet when his character arc blossoms, and his nature starts to evolve, we don’t see change sprouting at the very top of the pyramid, but lower toward the bottom.

HAIDREN TO BOREAL

Ah, our Boreali conundrum, at last.

There was no way to bring readers to Boreal and not grant ample deference to the society, liturgy, and sacraments that comprised her being. She is different than the other characters. Difficult, too. Residing in Boreal doesn’t shed light on her makeup, it peels back a curtain to the thriving ambiance of her soul. There are limitations, beautifully erected boundaries there, safeguarding her steps, protecting her from corruption. What most do not understand, is that Luscia not only honors these restraints…she cherishes each more precious than gold.

Sharing Zaethan’s diagnosis, many readers observe Luscia’s painstaking discipline and decide she is repressed. She denies herself what she most often wants, after all. Is that not a form of repression? Yes. At times, Luscia redraws the line she so carefully walks. But that struggle is also her freedom. Only those from devout faith communities understand the paradox holding Luscia in place: there is freedom in submission. Joy too. The crux is the subject of that submission. What Luscia adores, she will serve, even to the point of suffering. Her danger is adoring the wrong thing too much—which is precisely what readers think best. Were she to shirk those restraints, break out from her perceived repression, she would unravel. Her whole person would, in other words, break. There is no Luscia outside of this pyramid—not as we know her. And that is what fundamentally separates her from her peers.

Man’s Search For Meaning by Viktor E. Frankl has sold over 16 million copies since it’s original publication in 1946, after his release from the Nazi concentration camps (including Auschwitz). I recommend everyone reads it, if not once per year.

In his gut-wrenching, yet inexplicably hopeful, recount, Frankl reports that it wasn’t political devotions, humanism, or pure grit that equipped prisoners to survive the camps. It was their faith. Be they Jews sneaking strips of Torah into the lining of their trousers, Christians reciting Psalm 23 as they waited in line for the gas chambers, or even a man clutching the last photo of his wife before having it ripped away… faith in something beyond themselves was paramount to enduring hunger pains; festering wounds; routine beatings; rotting limbs; and horrors even Frankl refused to detail.

“Religion is the search for ultimate meaning.”

~Viktor E. Frankl

Whatever we believe in becomes the target commanding our focus. And faith, the arrow.

Unity in diversity doesn’t occur because we deny our differences. Or by redefining terms as to speak in a new, non-confrontational language. A unified team allows for diverse motives, undressed compromise, treaties of give and take. It says, “I see who you are, and I know I cannot change you. But even still, we must work together”. More often than not, everything depends on it.

Religion had to be at the forefront of Book 3 because it comprises the base of the pyramid upon which we rest. It formed the foundation beneath the haidren to Boreal’s feet. It tells Luscia exactly who she is and who she is not. And to she who is devoted to that whisper, it will always be enough.

“Thou hast made us for thyself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it finds its rest in thee.”

~Augustine of Hippo, Confessions

Experience these collisions firsthand in House of Boreal by embarking on your Orynthian journey today!